Thomas Waterman Wood

Thomas Waterman Wood (1823-1903): Montpelier’s Master Artist

Thomas Waterman Wood, Self Portrait, 1894

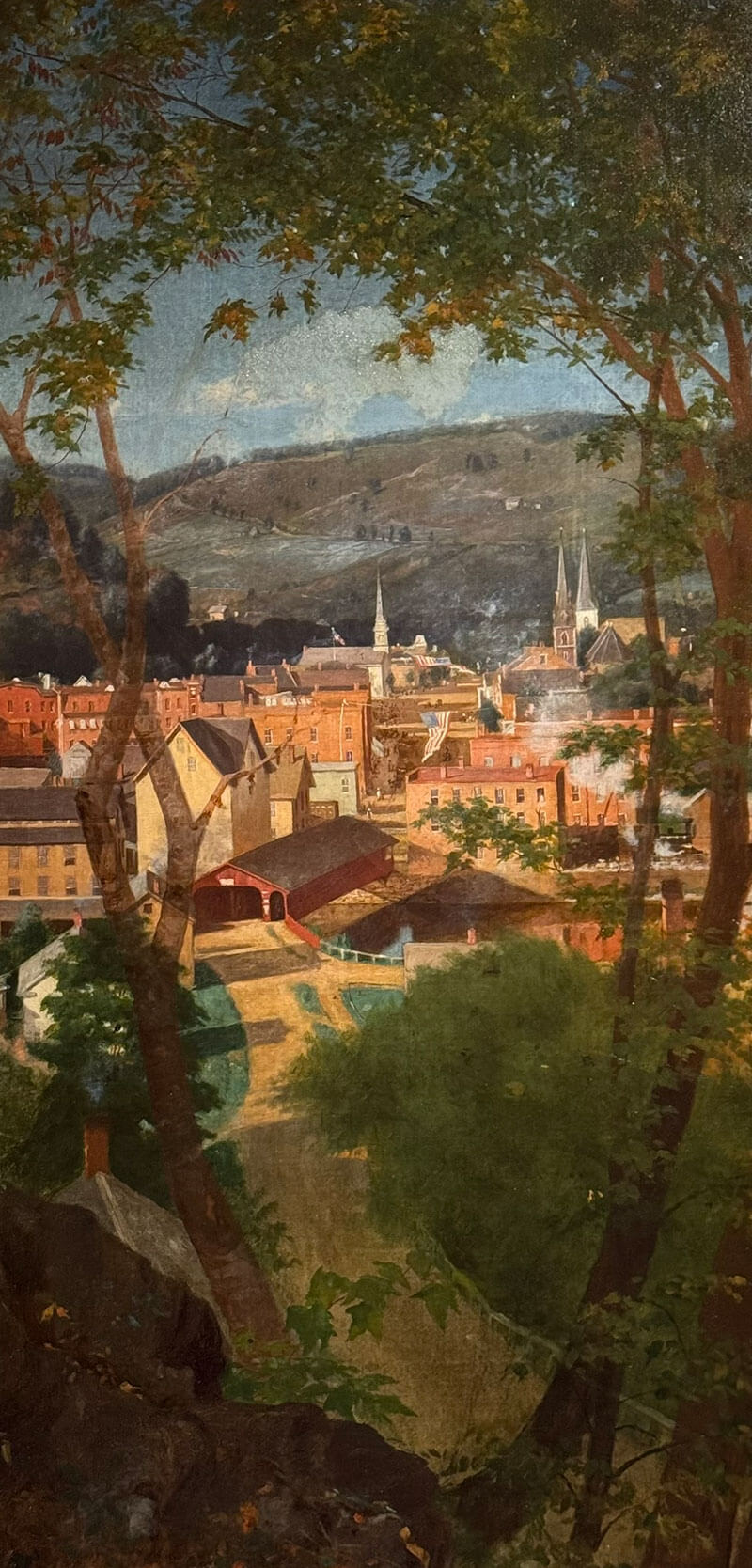

At the time of Wood’s birth in 1823, the capital boasted only about 2,400 residents and exposure to prevailing art and culture was scanty indeed.

Montpelier was a most unlikely birthplace for Thomas Waterman Wood, an artist who was to head both the National Academy and the American Watercolor Society — twin pillars of the traditional 19th century American art establishment.

Yet Wood, the son of a local cabinetmaker and largely self-taught save for a few months’ instruction in the studio of Boston artist Chester Harding, would steadily rise in both public approval and the respect of his fellow artists.

His capable work in portraiture was his bread and butter, but it was his shift into genre painting, skillfully capturing everyday scenes of rural New England, that brought him a more enduring reputation. Artists such as Norman Rockwell built upon the foundations laid down by practitioners such as Wood, Winslow Homer, J. G. Brown, and Eastman Johnson. And it is these works that still enthrall modern viewers.

Wood insisted upon drawing the specifics of his subject matter, rather than resorting to idealized types. The Art Journal of April 1876 declared: “As a colorist Wood is forcible, and as a delineator of character he never accepts the ideal, but goes direct to nature for his models. In the Composition of a picture, every object is clearly drawn, and he secures attention by the directness of his story.”

Working from a profusion of preliminary, unsigned sketches and studies, Wood meticulously assembled his larger story-telling paintings such as “The Village Post Office,” “The Quack Doctor,” and the “Yankee Peddler,” piece by piece from individual portraits, drawings of animals, and architectural features.

The complete whole became far more than the sum of the individual parts. Wood’s pictures captured events in the life of his Montpelier village or related compelling moral tableaux such as the accusing spouse imploring the saloon-keeper in “The Drunkard’s Wife.”

Wood also enjoyed delightful visual puns to accentuate the moral messages of his stories: a bevy of quacking ducks emerges from underneath the wagon of “The Quack Doctor,” and the final three letters in the name on the vehicle’s side, I. M. Cheatham, are obscured by the wagon wheel.

It would be impossible to understand Wood’s life and work without underlining his and his wife Minerva’s affectionate relationship to his hometown of Montpelier. Although Wood lived in New York City, and traveled widely around the country and Europe to execute his art projects, he returned every summer to Montpelier.

While established in the Pavilion Hotel or in his Gothic cottage “Athenwood,” Wood painted scores of Montpelier locals who would later inhabit his hugely successful paintings such as “Crossing the Ferry,” “Arguing the Question,” or “Jump.” His relentless Yankee ethic resulted in an outpouring of artistic works in oils, watercolors, and skilled etchings. In his frequent portrayals of African-Americans, as in “Southern Cornfield” and “The Faithful Nurse,” Wood avoided racial stereotyping, treating each figure individually.

He also took time to banter with his neighbors, or to toss surplus apples from his orchard to neighborhood children from the top of his retaining wall at Athenwood. (After his death in 1903, one of the floral tributes at his service bore the legend “Given by the children of Northfield Street.”)

The death of his wife in 1889, after decades of disability, ended a remarkably intimate relationship.

In his later years, Wood determined with the cooperation of his longtime friend, Columbia University professor John W. Burgess, to give his hometown an art gallery. It would include representative works of his own, as well as examples from artists such as William Beard, Asher B. Durand, J. G. Brown, F. S. Church, and Alexander Wyant.

Wood also traveled to the great museums of Europe to copy splendid works of Rembrandt, Raphael, Murillo, Titian, Turner and others. The results of these gifts live on today in the T.W. Wood Gallery: A Museum of American Art at 46 Barre St.

Wood represented the conservative wing of the American art establishment during his many years as the president of the National Academy. Artist James Smillie termed Wood’s faction the “old fogey element” because Wood and his colleagues were less enamored of the Impressionists and “French Tendencies.”

In vigorously portraying everyday characters, and creating vibrant story-telling pictures, few matched the sheer vitality and wonderful specificity of Wood. Each carefully rendered detail contributed to the resonance of the whole. His images of rural Vermont and the diverse natives of Montpelier continue to speak to audiences a century after Wood first drew these visions on canvas and paper.

Perhaps he failed to meet modern expectations that art should shake up societal norms. But his evocative work nevertheless holds a mirror to the past, allowing us, albeit imperfectly, to enter into its culture to recapture precious moments of everyday life.

This essay was adapted from “Thomas Waterman Wood: Montpelier’s Master Artist,” by Richard Hathaway, originally published in Montpelier’s Treasure: The Legacy of Thomas Waterman Wood, copyright T.W. Wood Gallery, 2008. Hathaway was a professor of Liberal Studies in the Adult Degree Program at Vermont College and served as a trustee to T. W. Wood Gallery.